Attack of the Juniper

/Spring is upon us here in Albuquerque—buds, blossoms, and allergies to boot. It seems everyone at the office is raiding the tissue stock, huffing nasal sprays, and bemoaning the side effects of Benadryl compared to Claritin.

Meanwhile… I’m fine. Which is odd, because I’ve always considered myself to be rather badly afflicted by seasonal allergies. Growing up I associated warm weather with the onslaught of familiar symptoms: dry eyes, tight scratchy throat, runny nose, and fits of sneezing.

Not this year! This is my first spring living in the Southwest, and apparently the region suits me. My old enemies, ragweed and grasses, don’t fare well in central New Mexico, so I’m safely removed by several hundred miles.

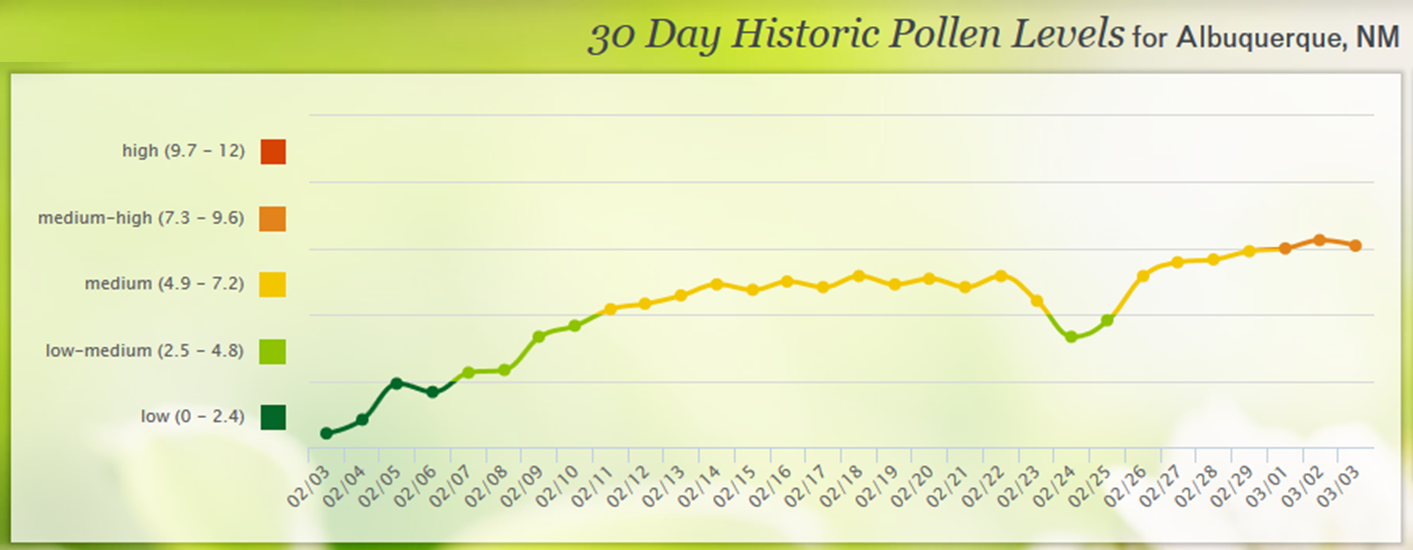

On the other hand, I’m right in the thick of a storm of pollen from other plants. Here the main offenders are trees like juniper, elm, cedar, and willow, with juniper pollen counts hitting particularly high levels in the last few weeks.

My different experiences of seasonal allergies in New York versus New Mexico just go to show that not all pollen is created equal, and not all people with allergies react to the same triggers.

The Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America estimates that anywhere from 10 to 30% of the global population experiences pollen-induced allergic rhinitis, in which airborne grains trigger inflammation in the nasal cavities. Specifically, a type of white blood cell called the mast cell catches the particles and, identifying them as foreign invaders, sounds the alarm by releasing histamine and leukotrienes. These chemicals tighten airway muscles, stimulate mucous production, and cause nasal blood vessels to “weep” more fluid. On top of feeling stuffy and runny, you’ll find all the swelling and irritation triggers the sneeze reflex. (Gesundheit!)

Ideally, this inflammatory response kicks in as needed to protect you by flushing out your respiratory passages. If you did inhale something dangerous, like a burst of smoke and ash, you’d be grateful for your body’s wheezing-weeping-sneezing reflex! But an allergy is by definition an overreaction to a stimulus that’s inherently harmless. Pollen is much maligned for inflicting so much suffering on us this time of year, but it’s actually innocuous in and of itself, as evidenced by the fact that so many people continue to inhale pollen (and pet dander and peanut particles) without blinking an eye. The villain here isn’t really pollen, it’s our own out-of-control immune systems.

Of course, pollen is still the obvious trigger, and unlike that brief burst of smoke, it hangs around for months, wafting and clinging and getting inhaled. Hence all the complaints from sniffly colleagues who have been dealing with high pollen counts for days on end.

I can’t stop marveling at the fact that, while these longtime Burqueños are clearly sensitive to juniper pollen, my respiratory system seems oblivious and unresponsive. It’s as if my immune system learned to recognize the clouds of allergens that I inhaled as a child, but isn’t aware of the new stuff that’s in the air now. Am I just genetically lucky, or did my immune system “inoculate” itself against the pollen of New York and not the pollen of New Mexico? It’s possible (though to quote the AAFA, “It should be cautioned that this is an area of early research so claims should be taken with a grain of salt”).

Allergy season is just beginning, of course, so I’ll have all spring and summer to see if other local tree and grass allergens affect me. Come fall I might even find that I react to the pollen of Russian thistle, also known as tumbleweed. Unpleasantness aside, I think as a newcomer to the Southwest I’d be pretty amused by the novelty of a tumbleweed allergy! Only time will tell.

This post was brought to you by the New Mexico Allergy Society, the Asthma and Allergy Foundation of America, and some deep breaths of relief.